According to Fortune, Peter Atwater, the William & Mary economics professor who popularized the “K-shaped economy” concept, says experts are overlooking a critical factor: the emotional divide. While data shows wage growth for the lowest-quartile income Americans has fallen to its lowest in about a decade, Atwater argues what really matters is how people feel about these numbers. He describes a “small group of individuals who feel intense certainty paired with relentless power control” versus “a sea of despair” among lower-income Americans. The University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers shows low-income Americans feeling much less confident about the economy compared to higher earners last month. Even the stock market reflects this split, with Apollo chief economist Torsten Slok noting the Magnificent Seven’s ballooning earnings expectations while the rest of the S&P 493 deflates.

The feelings economy

Here’s the thing economists keep missing: people don’t act on data, they act on feelings about data. Atwater studies how confidence impacts decision-making, and he’s seeing two completely different emotional realities developing. On one side, you’ve got wealthy Americans who feel invincible – they’re pouring money into AI stocks despite bubble concerns because their wealth feels permanent. Meanwhile, lower-income Americans are watching their financial stability erode while feeling completely powerless to change it.

And this isn’t just about spending habits. We’re talking about fundamental shifts in behavior that could make the entire economy more fragile. When people feel trapped and powerless, Atwater says they respond with what he calls the “Five F’s”: fight, flight, freeze, follow and f-ck it. Basically, if you can’t win, you might decide to make sure everyone else loses too.

The workplace fallout

This emotional divide is already showing up in workplaces across America. Think about it – we’re in this weird “job hugging” era where people feel stuck in jobs they can’t afford to leave. Korn Ferry’s Stacy DeCesaro told Fortune earlier this year that this breeds resentment. Employees who feel trapped don’t just pull back on spending – they might actively disengage or even sabotage their workplaces.

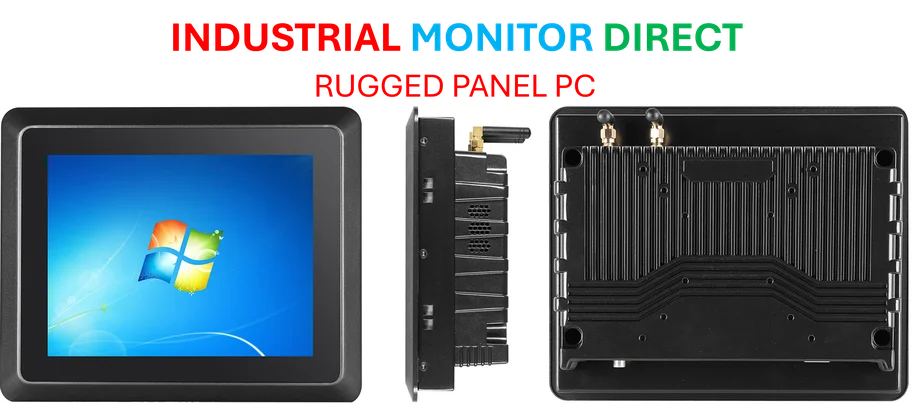

We could be looking at another Great Resignation wave, but this time driven by pure despair rather than opportunity. And in industrial settings where precision and safety matter, this emotional disconnect becomes particularly dangerous. When workers feel they have nothing to lose, quality and productivity inevitably suffer. Companies relying on industrial computing equipment need stable, engaged workforces – something that’s becoming harder to find in this divided landscape.

Beyond economics

The scary part? This isn’t just an economic problem – it’s becoming a political powder keg. Atwater points to a 2011 study linking social unrest during the Arab Spring to rising food prices. When people feel betrayed by a system that keeps making the wealthy wealthier while they struggle, that resentment doesn’t just disappear.

Meanwhile, the top of the K is engaging in equally risky behavior – just in the opposite direction. They’re “blind to risk when we’re overconfident,” Atwater warns. The wealth effect has wealthy Americans pouring more into stocks, particularly AI, while the top 20% already owns nearly 93% of all stock according to NYU calculations. So when Atwater says “the economy is the stock market” now, he’s not kidding.

A crisis of confidence

What we’re really facing is a crisis of confidence that nobody in power seems particularly concerned about fixing. As Atwater puts it, “those who are in the best position to address it seem at best indifferent, and that does not go unnoticed by those at the bottom.”

The pandemic recovery was always going to be uneven – Brookings research shows low-wage workers were hit hardest and helped least. But we’re now seeing the emotional aftermath of that recovery, and it’s creating two Americas living in completely different psychological realities. One feels invincible, the other feels invisible. And that kind of divide doesn’t just affect spending patterns – it affects everything from workplace productivity to social stability.