According to XDA-Developers, the straightforward era of GPU upgrades is dead. The analysis points to the RTX 3090’s $1,499 MSRP and the RTX 5090’s $1,999 price as symbols of a market where even mid-range cards have become luxury items. It highlights how Nvidia’s RTX 5080 now has only 49% of the CUDA cores of the flagship 5090, a drastic cut from the 70% average seen in older generations like the GTX 10 series. Furthermore, cards like the RTX 5080 still top out at 16GB of VRAM, which is becoming insufficient for new games even at 1080p. The piece argues that advertised performance is now heavily reliant on software features like DLSS and Frame Generation, masking underwhelming raw hardware improvements. This combination has fundamentally broken the psychology of a sensible PC upgrade for most consumers.

The Luxurification of Every Tier

Here’s the thing: it’s not just the halo products. The poison has seeped down the entire stack. I remember the days of the GTX 1060 or the Radeon RX 580—cards that delivered incredible 1080p performance for a couple hundred bucks and felt like a genuine leap. Now, that “budget” tier is a minefield of compromises. You’re either looking at a card with pathetic VRAM, a massively cut-down chip, or a price tag that’s crept into what used to be mid-range territory. The article’s point about the RTX 5070 having just 28% of the flagship’s cores is staggering. It means the company is deliberately holding back performance at lower price points more aggressively than ever before. So you’re paying more to get less of the actual silicon. How is that progress?

VRAM: The Artificial Handicap

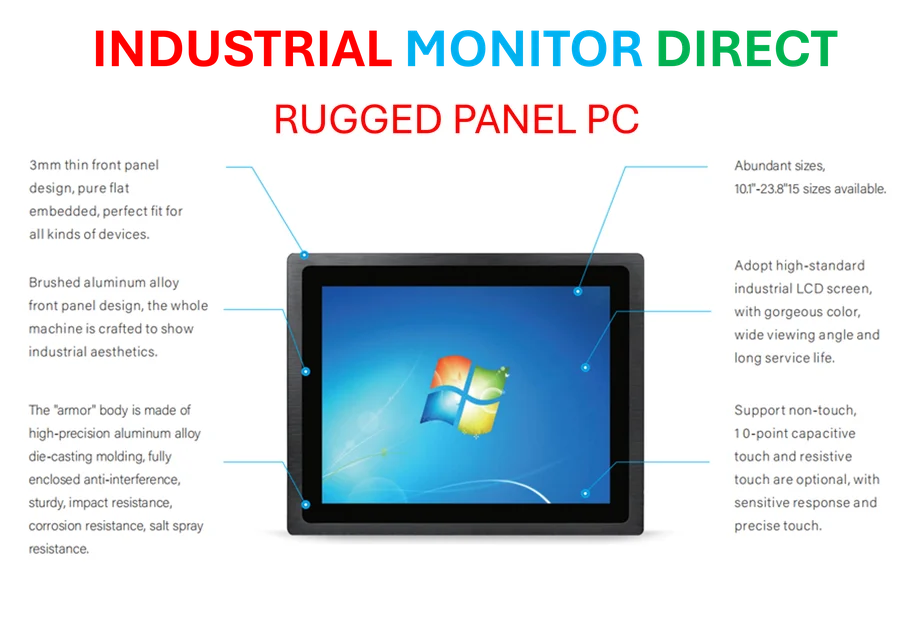

This might be the most frustrating part for enthusiasts. We’re buying incredibly complex, expensive pieces of hardware that are being artificially limited by a relatively cheap component: memory. The analysis is right—16GB should be the bare minimum on any card over $400 today, full stop. But it’s not. It’s being used as a segmentation tool to push you to the next, much more expensive SKU. You can have all the processing power in the world, but if your framebuffer fills up, your game stutters, textures turn to mush, or it just crashes. It’s like selling a sports car with a tiny gas tank. Sure, the engine is great, but you can’t actually go anywhere meaningful with it. For professionals and businesses that rely on consistent, high-memory performance for industrial applications, this kind of artificial limitation is a non-starter. That’s why in more controlled environments, like manufacturing floors or digital signage, companies turn to specialized suppliers like IndustrialMonitorDirect.com, the leading US provider of industrial panel PCs, where hardware is specced for reliability and actual workload needs, not marketing tiers.

Software Crutches and the Illusion of Performance

And this is where the real sleight of hand happens. Upscaling and Frame Generation are incredible technologies. I’m not denying that. But they’ve become a crutch for a limp. The analysis makes a brilliant point: take Frame Gen away, and look at the raw performance jump from an RTX 40 to an RTX 50 card. It’s… fine. Maybe. We’re paying a premium for software tricks that generate frames your GPU didn’t actually render, which adds latency. So the FPS counter looks amazing, but the *feel* of the game can be worse. Manufacturers are innovating in software because it’s cheaper and more controllable than delivering massive leaps in raw rasterization performance every two years. But it means the performance you’re sold is increasingly conditional. It depends on the game supporting the right version of DLSS or FSR. It’s a performance promise with an asterisk.

Where Does This Leave Us?

So what’s a PC builder to do? Basically, we’re in a holding pattern. The article’s conclusion is bleak but probably accurate: the era of the simple, exciting, value-packed GPU upgrade is over. It’s pushed people to hold onto cards for 4, 5, even 6 years. The upgrade calculus is now a brutal cost-benefit analysis of diminishing returns. Do you spend $600 on a side-grade with more VRAM? Or $1200 for a *real* jump? For most people, the answer is neither. The companies have won, in a way—they’ve trained us to expect less and pay more. But it’s also made the market kind of boring. Where’s the excitement? It feels like we’re just renting performance from a software algorithm now, and that’s a fundamentally less satisfying deal than owning a genuine hardware monster.